Definition of Love Making was Rated G in 19th Century

Definition of Love Making was Rated G in 19th Century

.

A quote by the Reverend George W. Hudson in his 1883 book sounded rather scandalous, but wasn’t. As an illustration, the good reverend said “making love” and didn’t mean in a sexual way. It’s essential to note that the term had a very different meaning in the 19th and early 20th centuries than now.

.

Fine Example

.

“Courtship, properly, has but one object, viz., marriage; for it is nothing more nor less than love-making, and, no young man has a right to proffer his love to a young lady, nor ask hers in return, except with the intention of making her his wife.”

.

~ Reverend George W. Hudson, The Marriage Guide for Young Men: A Manual of Courtship and Marriage, 1883, p. 57

.

.

Common Phrase with Frequent Use

.

George Hudson, a minister, wasn’t the only one to use this term. Despite today’s definition, use was prominent in the 19th Century United States, England and her holdings (such as Australia and Ireland). Definition of Love Making was Rated G in 1800s

Examples follow, in chronological order.

.

1822

.

The phrase / term “love making” was in use as early as 1822 when in Poughkeepsie, New York, the Poughkeepsie Journal, on 11 September (1822) reported the most unfortunate swindling of a widow of 2 months of her savings, wealth, and comforts of home. A boarder came into her home nearly penniless. He charmed her with sweet talk, kisses, promises, words of love, and promises of marriage to come. He’d repay her well, and wed her just as soon as he reconciled with his wealthy father. Because all of his lovemaking efforts were lies, he left her destitute.

.

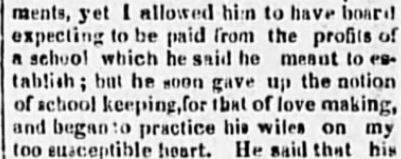

Even though the print of the article did not scan well to digital, likely owed to the age of the newspaper (nearly 200 years old), here’s a snippet of the phrase in context:

.

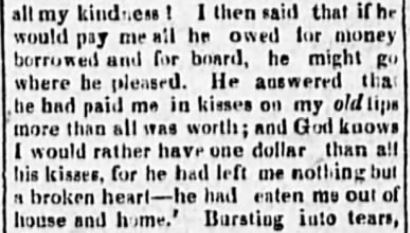

Love making is used in context~ A snippet from Poughkeepsie Journal, part 1. (11 September, 1822)

.

A transcription of the above snippet, in case it’s too difficult to decipher:

.

“…I allowed him to have board expecting to be paid from the profits of a school which he said he meant to establish; but he soon gave up the notion of school keeping, for that of love making, and began to practice his wiles on my too susceptible heart…”

.

Then, a few paragraphs later…

.

Regrets of love making~ Another snippet, a few paragraphs later from Poughkeepsie Journal (on 11 September, 1822).

.

A transcription of the above snippet, in case it’s too difficult to decipher:

.

“I then said that if he would pay me all he owed for money borrowed and for board, he might go where he pleased. He answered that he had paid me in kisses on my old lips more than all was worth; and God knows I would rather have one dollar than all his kisses, for he had left me nothing but a broken heart–he had eaten me out of house and home.”

.

The article is quite lengthy. Enough to show that a friend of the family, an attorney, had no trouble standing by her story as the truth. As a result, Widow Destitute had not lost her reputation one wit while the cad went to jail. Hence, it’s conceivable that the term meant the same in 1822 as it did in 1860.

.

1835

.

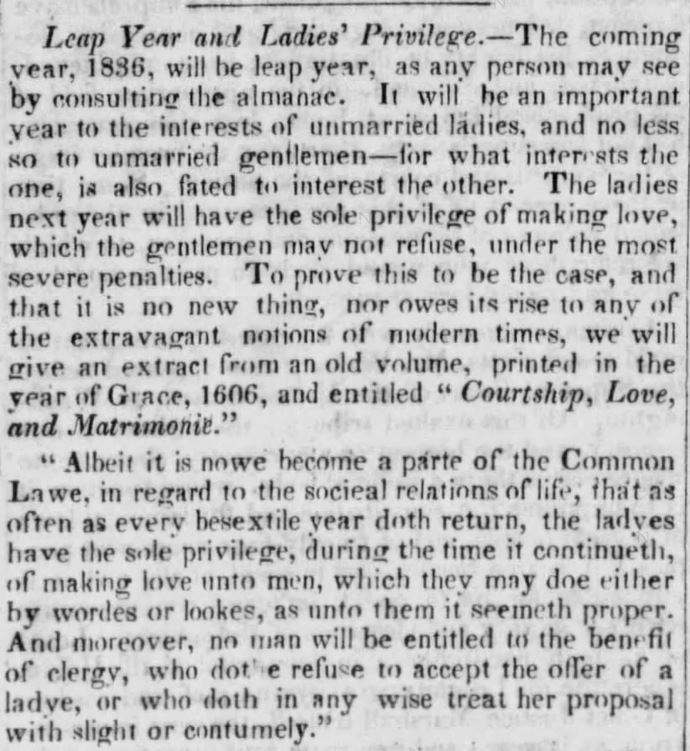

The following article appeared in The Long-Island Star of Brooklyn, New York in December of 1835. In context of leap-year’s traditions, “love making” is obviously innocent. The phrase clearly means courtship, showing interest, making social invitations, gift-giving.

.

In context, I believe it’s clear the definition of Love Making, in 1835, was fully Rated G.

.

Opening 2 paragraphs of an article (including minimal header as was typical of the era) published in The Long-Island Star of Brooklyn, New York, on 15 December, 1835. “The ladies next year have the sole privilege of making love, which the gentlemen may not refuse.”

.

This newspaper quote from The Long-Island Star of Brooklyn, New York on December 14, 1835 references Leap-Year Traditions. “The love-making privilege… cannot make love during that tedious interval…”

.

1860

.

A newspaper article titled St. Valentine’s Day appeared on 15 February, 1860 in The New York Times. A brief line from the lengthy piece reads:

.

“…The decline and fall of St. Valentine is a not altogether wholesome sign, for it implies, we fancy, not that love-making is going out of fashion, but that it is growing less tender and fanciful than of old–a change by no means to be commended. When all days and all seasons are Valentine’s days, we may be sure that none will be.” [emphasis added]

I submit that no newspaper of 1860 would have printed an article with today’s casual term lovemaking (spelled any way at all: one word, hyphenated, or two words) in today’s context. Reputable papers chose delicate euphemisms for anything remotely related and always kept language Rated G.

.

1879

.

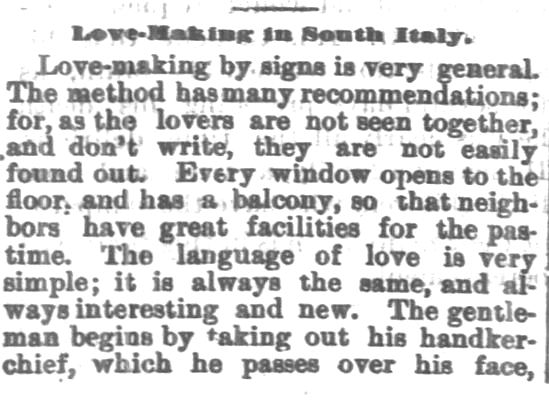

Note the flirtation with handkerchiefs, blushes hidden by fans, and more. Historical romance fans are familiar with “Language of the Fan.” And “Language of the handkerchief,” too. Victorians also spoke the “language of flowers.” Because they were well known, all ‘languages’ assisted swains with lovemaking in the 1800s.

.

Love-making in South Italy, Part 1. From Chetopa Advance of Chetopa, Kansas on March 27, 1879.

Love-making in South Italy, Part 2. From Chetopa Advance of Chetopa, Kansas on March 27, 1879.

Part 3: Love-making in South Italy. From Chetopa Advance of Chetopa, Kansas on March 27, 1879.

.

1880s

.

Lovemaking in a G-Rated Context: “Every Man Original in Love-Making“. Probably there is no instance in which any two lovers have made love in exactly the same way as any two other lovers since the world began.” (Sir Arthur Helps) From Proposal and Espousal, A Christian Treatise. Published, 1880s. Now public domain.

.

1893

.

Law and Courting, part 1. From St. Louis Post-Dispatch on December 31, 1893. “The business of making love is one with which the courts should interfere as little as possible…”

Law and Courting, part 2. From St. Louis Post-Dispatch on December 31, 1893. “The business of making love is one with which the courts should interfere as little as possible…”

.

1895

.

Quip about big balloon sleeves of the mid 1890s being Not Conducive to Happiness (see title of illustrated quip), because “these you have on,” her beau says, “ain’t intended for love makin’.” A fine example of the common use and Rated G classification of the phrase “Love Making.” From The Horton Headlight-Commercial of Horton, Kansas on July 18, 1895.

.

Common Use Remained into the 20th Century

.

1910

.

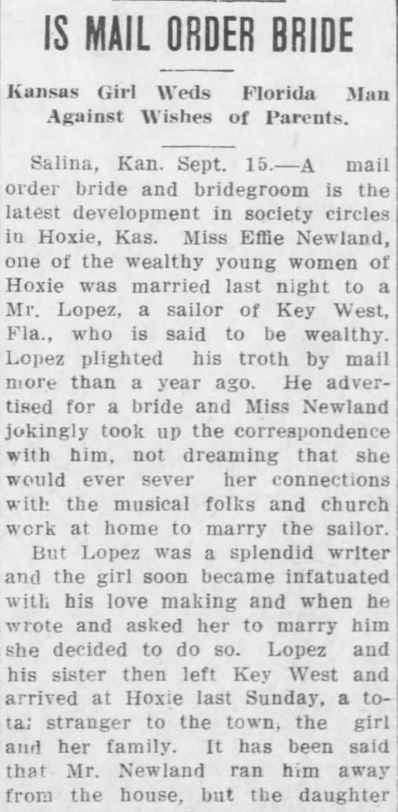

Kansas Girl became infatuated with Florida Man’s Love Making, Part 1. The Leavenworth Post of Leavenworth, Kansas on 15 September, 1910.

Part 2. The Leavenworth Post of Leavenworth, Kansas on 15 September, 1910.

.

“Lovemaking” in Sweet Historical Romance

.

I gathered my bravery about me and used the term “lovemaking” in my sweet (wholesome) romance novella, WANTED: Midwife Bride, my contribution to the Timeless Romance Anthology: Mail Order Bride Collection. Readers would either understand the context of the 19th and 20th centuries, or they wouldn’t–and would take today’s common definition. Either way, I believed the phrasing would be “mild enough”.

.

On the one-week anniversary of their wedding, Naomi walked home from the clinic, hand in hand with her husband. The sun had begun its slow descent, taking with it the oppressive heat of the day. Shadows lengthened.

.

Already, the depth of intimacy between them astounded her. One year and eight months with Ernie and she’d never felt so close, so well-known, so… cherished. The growing tenderness between them was sweet, and Joe’s lovemaking reached her heart.

.

~ first 2 paragraphs of Chapter Ten, WANTED: Midwife Bride, by Kristin Holt, Copyright © 2015-2016.

.

.

Invitation

.

What do you think? Had you understood the term / phrase in 1800s definition?

As used in my two paragraphs above, within my recent publication (WANTED: Midwife Bride), if considered in today’s language, is it too much for a PG-rated (or milder) novella? Your honest opinion is all that matters.

.

.

Related Articles

.

.

Updated May 2022

Copyright © 2016 Kristin Holt LC

Definition of Love Making was Rated G in 19th Century