Victorian America’s Oleomargarine

.

Some folks loved it. Some folks hated it. No matter a person’s opinion, Victorian America’s Oleomargarine made quite the impression on consumers.

.

.

Yes! Fake butter swamped the Victorian-era United States. The new invention was both abhorred and adored. Margarine may have begun in France, but U.S. manufacturers grabbed that bull by the horns and ran with it. An American inventor bought the patent, then patented improvements to the counterfeit butter process.

.

Oleomargarine is not butter, it’s:

Bull Butter (because bulls don’t give milk).

Ox Butter.

Bogus Butter.

Beef-suet Butter.

Suet Butter.

Artificial Butter.

Manufactured Butter.

Patent Butter.

Tallow Butter.

Counterfeit Butter.

Slaughter-house Butter.

Soap-fat Butter.

Oleo.

Oleo-margarine Butter.

Oleothingumbob (Times Union of Brooklyn, New York, April 24, 1874).

Butterine.

Oleocephaline (seal fat butter) (Los Angeles Herald, Los Angeles, California, February 3, 1874).

.

Ah, the many names for “margarine” from Victorian-era newspapers.

.

The French Started Fake Butter

.

As reported in Nashville Union and American, of Nashville, Tennessee on December 20, 1872:

ARTIFICIAL BUTTER.

The French are ingenious in their preparations of food. They are most successful in the art of deceiving the palate with substitutes which cost less than the genuine article.

.

Apparently the French Navy desired “some wholesome substitute for butter.” Napoleon III offered a prize to any inventor who created a successful alternative.

.

The article continues:

Mège Mourièz, after a long course of experiments, has succeeded in producing an excellent substitute for genuine butter that does not become rancid with time, and is otherwise highly recommended.

.

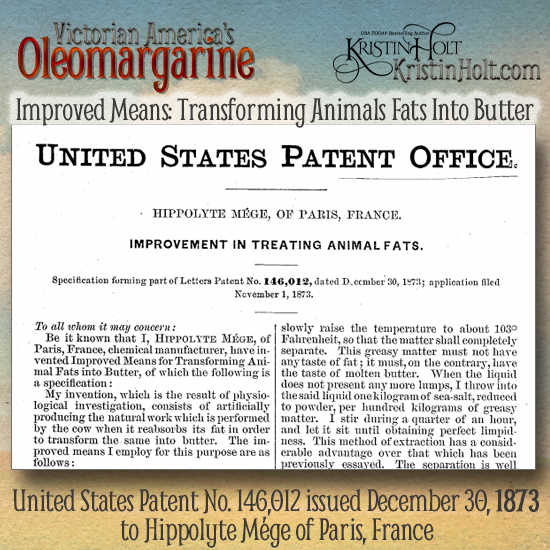

According to Britannica, “The French chemist H. Mège-Mouriès developed margarine in the late 1860s and was given recognition in Europe and a patent in the United States in 1873.” National Geographic states that competition happened in 1869.

.

Heading of United States Patent awarded to Hippolyte Mège for Improvements in Treating Animal Fats (Transforming Animal Fats into Butter). No. 146,012, dated December 30, 1873.

.

An American Quickly Followed Suit

.

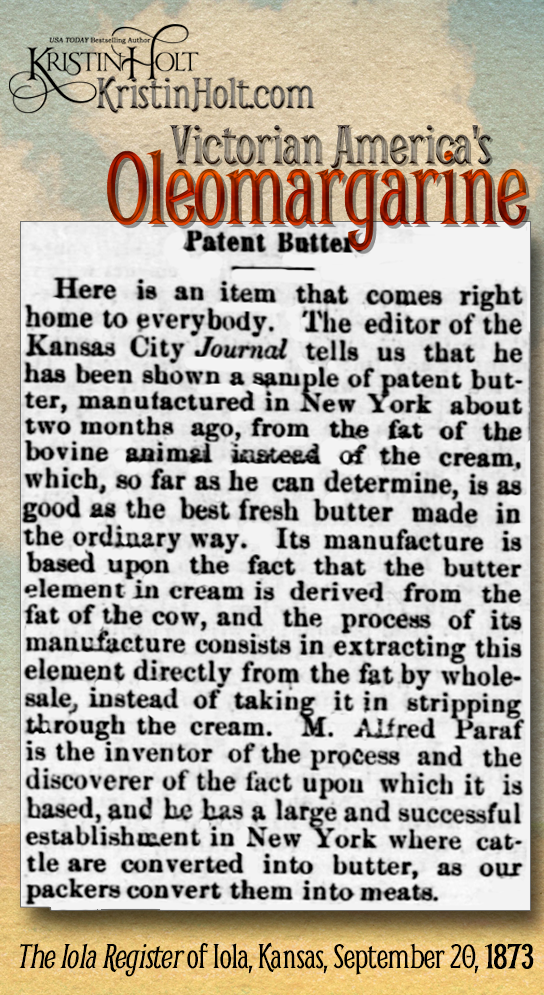

In an article titled Patent Butter, published in The Iola Register of Iola, Kansas on September 20, 1873, a fellow named M. Alfred Paraf of New York was cited as the ‘inventor’ of patent butter:

.

.

A glance at United States Patent No 137, 564, dated April 8, 1873, specifies that Alfred Paraf made improvements to the rendering process of beef fat in the creation oleo-margarine. Note that this guy shows up again in the “counterfeit butter is scrumptious” section, below, where he “expects that the new product will drive live cow butter out of the market altogether.”

.

Patent Butter

.

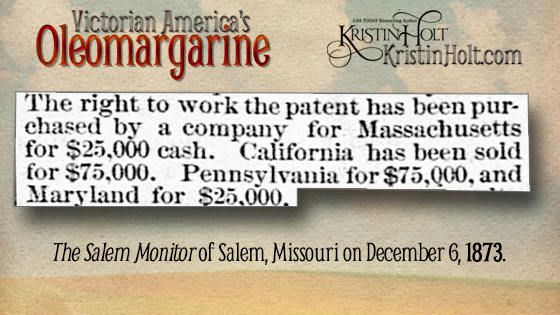

The United States Dairy Company purchased Mege’s French Process and were granted a patent on the process. This notice appeared on both the east and west coasts of the States and in between.

.

.

Why? Wasn’t Real Butter Enough?

.

With all those cows in sheds, all the skill and talent of small-batch homemade butter, why would anyone want anything but the real deal?

.

Nineteen century butter pat. Image: Courtesy of Object Lessons.

.

Butter factories (the real dairy kind, made from the cream of bovine milk) were already a growing industry in the United States before the War Between the States. Factory butter, widely considered superior to homemade, quickly took hold in the market.

Yet an increasing and steady supply of good butter wasn’t enough. Shortages still occurred.

In fact, Mége Mouriés (the Frenchman credited with inventing margarine) did all that work with beef tallow and churns “in an attempt to alleviate shortages of butter… He called it oleomargarine because its main ingredients were beef fat (called oleo) and margaric acid. Oleomargarine quickly became popular in northern Europe and the United States.” [SoyInfoCenter.com]

Many reasons seem to contribute to the success of Victorian America’s Oleomargarine: lower prices, ready availability no matter the season, and longer shelf-life without rancidity.

Okay. I understand shelf life as a selling point. Especially in the days of iceboxes and storing home-churned butter in the well or spring house.

.

Manufacturing of Victorian Oleomargarine

.

By the time the first Oleo-margarine factory fired up in the 1870s in New York City, commercially produced dairy butter was already well-known. In fact, factory butter was widely believed to be superior to most grades of farm-made or homemade butter.

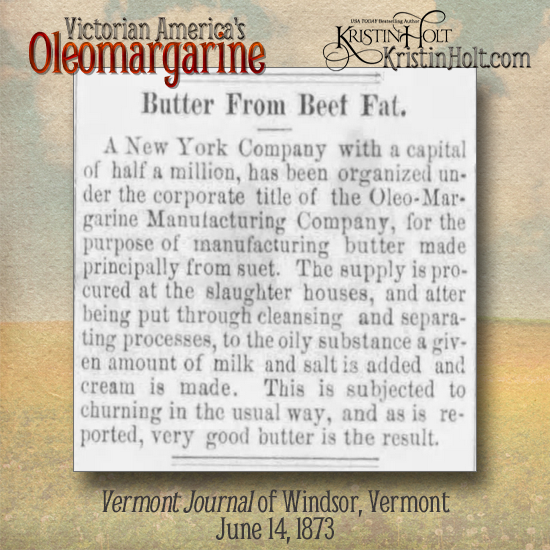

Factories quickly produced a ton of suet butter daily (The Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 June 1874).

.

.

The simplified “Butter from Beef Fat” process, explained above, leaves out a bit of detail. See this report from The Cincinnati Enquirer for more information:

.

1 of 3: The Cincinnati Enquirer of Cincinnati, Ohio on May 14, 1874.

2 of 3: The Cincinnati Enquirer of Cincinnati, Ohio on May 14, 1874.

3 of 3: The Cincinnati Enquirer of Cincinnati, Ohio on May 14, 1874.

.

The Nebraska State Journal of Lincoln, Nebraska (16 January 1874) stated:

Oleomargarine is what they call suet-butter, and 4,000 tons (8,000,000 pounds) of it have been wriggled down people’s throats in this country during the last eight months.

.

What were Oleomargarine Factories Like?

.

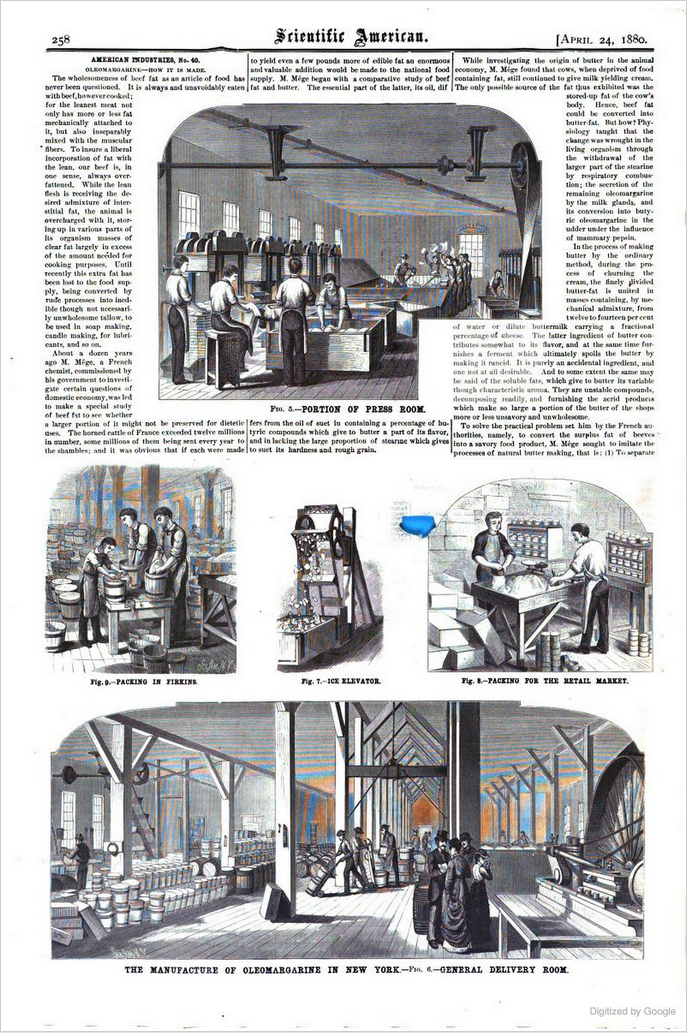

Illustration of The Manufacture of Oleomargarine in New York, published in Scientific American on April 24, 1880. [Image Source] Note the ice elevator in center of page.

.

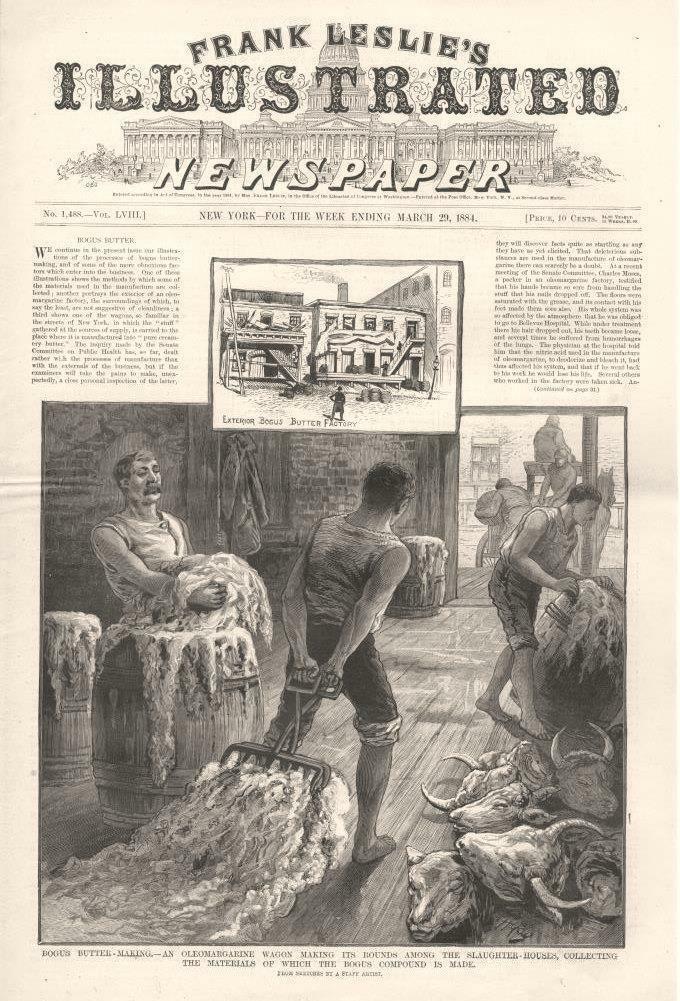

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, No. 1,488–Vol. LVIL, New York–for the week ending March 29, 1884. Beginning of an article titled Bogus Butter, with illustrations of Bogus Butter Making: An Oleomargarine wagon making its rounds among the slaughter-houses, collecting the materials of which the bogus compound is made.” [Image Source]

.

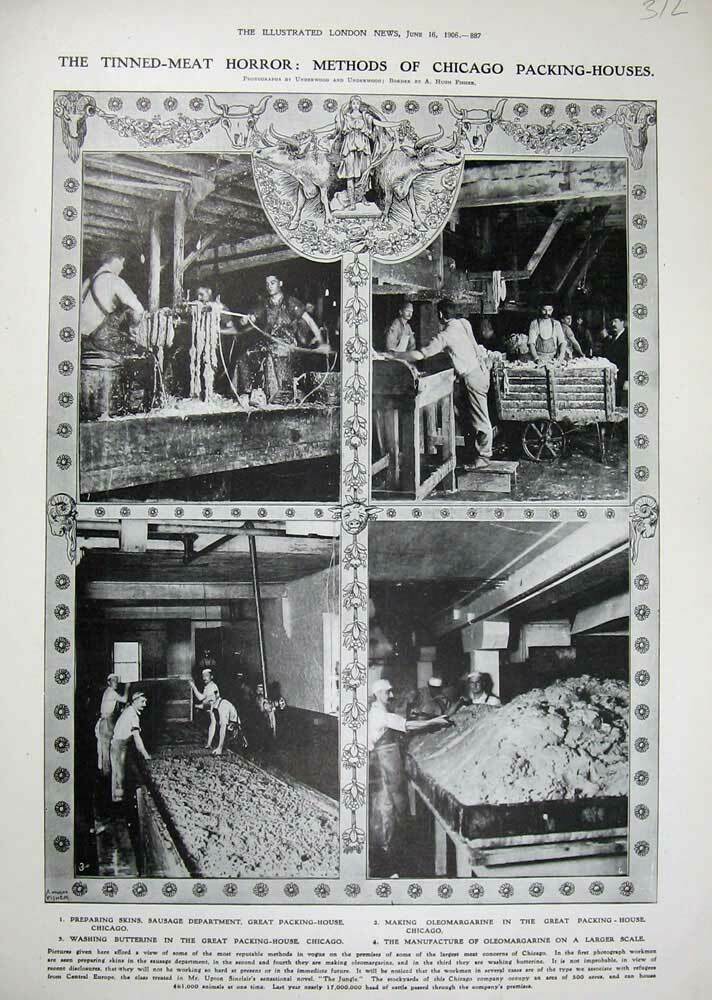

1906 photographs of Oleomargarine Factory. “The Tinned-Meat Horror: Methods of Chicago Packing-Houses.” 1. Preparing skins, sausage department, Great Packing House, Chicago. 2. Washing Butterine in the Great Packing House, Chicago. 3. Making Oleomargarine in the Great Packing House, Chicago. 4. The Manufacture of Oleomargarine on a Larger Scale. From The Illustrated London News on June 16, 1906. [Image Source]

.

Victorian Oleomargarine on the East Coast, West Coast, and In Between

.

Victorian America’s Oleomargarine factories may have begun in New York City, but they quickly spread. Newspaper accounts chronicle the arrival of an oleomargarine factory started at Bridgeport, Connecticut (The Boston Globe, May 20, 1874). Another factory, announced as under successful operation, began at Cincinnati (Decatur Weekly Republican of Decatur, Illinois, May 21, 1874).

.

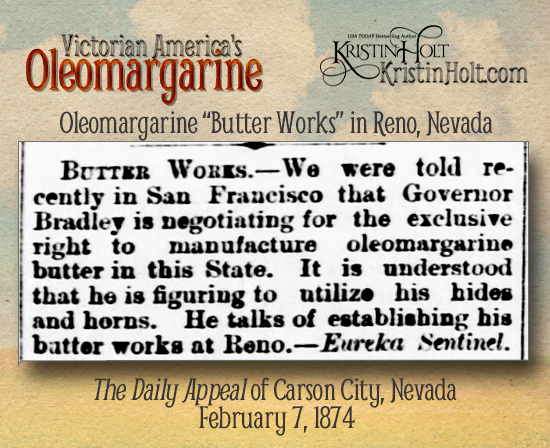

San Francisco soon opened a factory (The Sacramento Bee, September 23, 1873). Another was announced in Reno, Nevada.

.

The Daily Appeal of Carson City, Nevada, February 7, 1874,

.

.

Victorian Margarine Tastes Like Butter

.

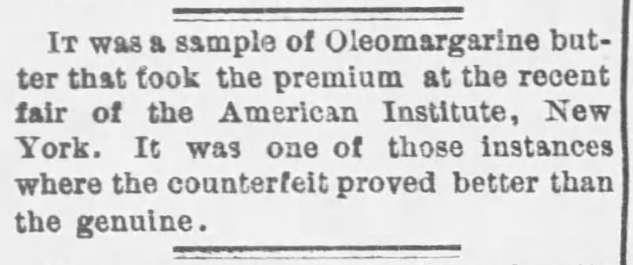

Oleomargarine won a premium at the fair of the American Institute. From The Kansas City Times of Kansas City, Missouri on December 18, 1878.

.

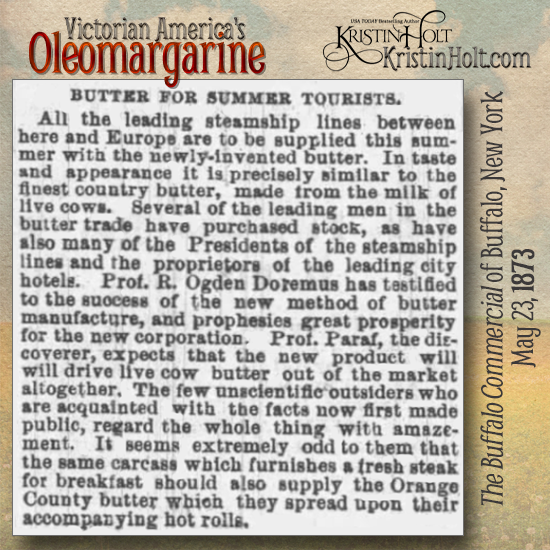

It’s so delicious, claimed numerous newspaper writers (and advertisers) that the real deal will be obsolete any day now. The following article from The Buffalo Commercial (1873) claims “several of the leading men in the butter trade have purchased stock (in newly-invented fake butter), as have also many of the Presidents of the steamship lines and proprietors of the leading city hotels.”

That’s quite an endorsement of Victorian America’s Oleomargarine. What are the chances, do you suppose, that this wholesale acceptance actually occurred?

.

.

The Elk County Advocate of Ridgeway, Pennsylvania on October 15, 1874.

.

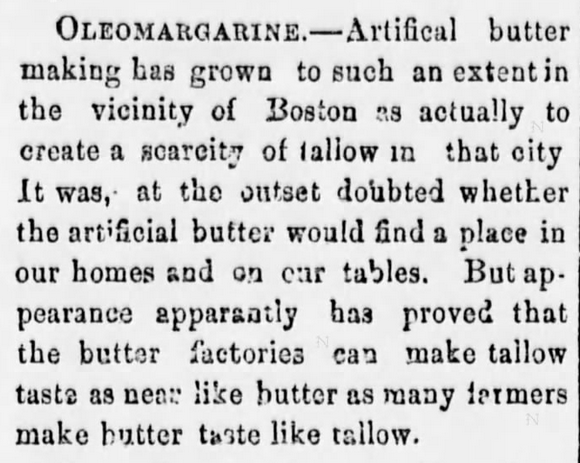

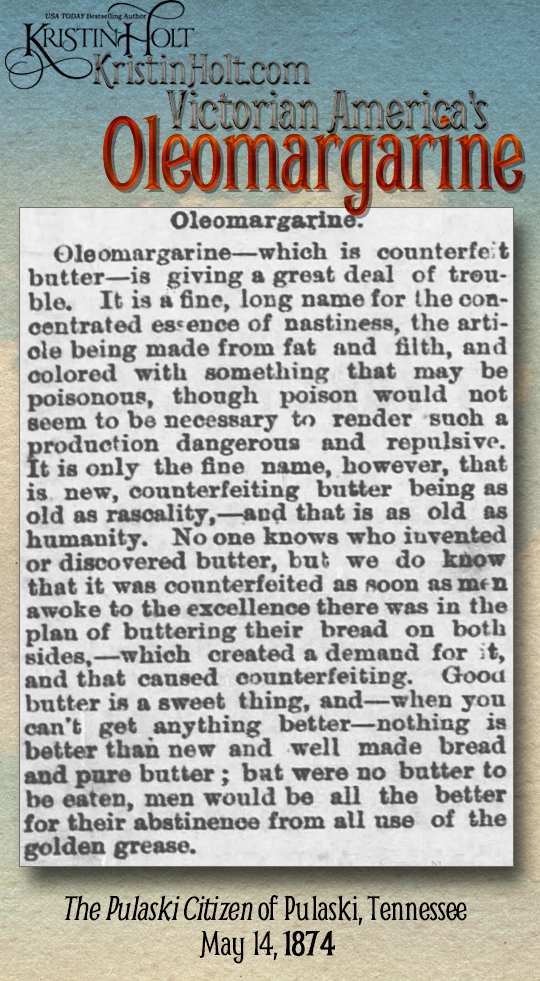

Oleomargarine Absolutely Does Not Taste Like Butter

.

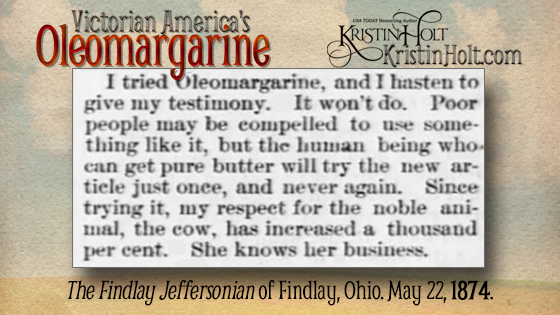

.

.

Oleomargarine is Identical to Butter

.

Looking back at the late nineteenth century, we find chemists’ conclusions that butterfat is butterfat. Scientists of the day claimed that the contents of Victorian American Oleomargarine were not only wholesome and pure but identical to the best quality butter.

.

Many chemists will maintain that butter is essentially the suet of the cow, obtained from the milk, where it is held in emulsion. The butter from milk contains less margarine than the suet. The process of making artificial butter consists in taking the freshest beef suet, separating most of the margarine by pressure, emulsing [sic] the residue with milk, and then separating the true butter from the emulsion. The flavor and odor of diary butter is due to two of three substances, which exist also in the suet. It is stated that the best beef-suet butter has all the characteristic fragrance of dairy butter.

.

The real trouble is that poor beef-suet and other fats may be used for the manufacture of so-called butter. There can be no doubt that artificial butter, prepared in the best manner, as above, would be more healthful and palatable for cooking than poor diary butter. It is useless to stigmatize such a product as “oleo-margarine.” The unregenerate and the practical chemists, and also the juries, will be apt to look upon it as “butter.”

.

The Galveston Daily News on April 15, 1874

.

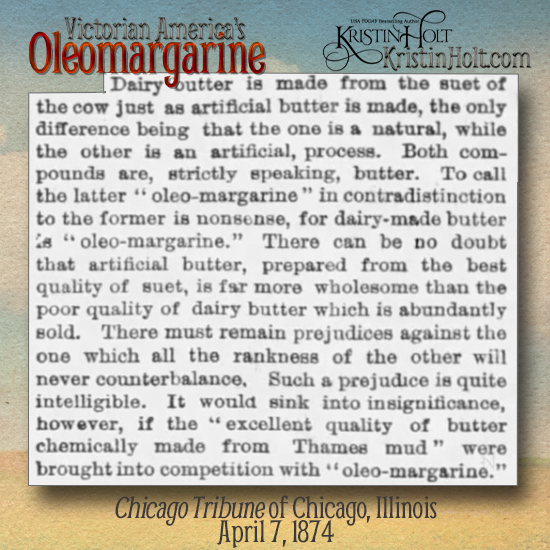

The Chicago Tribune published an article on April 7, 1874, wherein the writer insisted that butterfat was butterfat. The only difference between oleomargarine and dairy butter? How the fat was extracted. Either by manual efforts from slaughterhouse trimmings or by the cow’s milk-secretion glands.

.

.

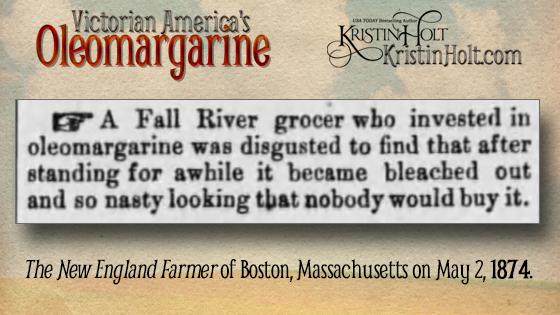

Oleo is So Not The Same as Butter

.

.

I’ll make do without, thanks.

.

.

It is not claimed that the article is good enough for table use, but that it is an excellent and economical substitute for cooking butter. A Cincinnati chemist, who has analyzed the oleomargarine, declares it “a very good substitute for butter in culinary and pastry purposes, free from rancidity, of palatable taste, and perfectly harmless.”

.

Decatur Weekly Republican of Decatur, Illinois on May 21, 1874

.

Oleomargarine: Cheaper Than Butter

.

The Iola Register of Iola, Kansas, claimed prices wouldn’t exceed fifteen cents per pound:

Sad but true, most price listings for Victorian America’s Oleomargarine are well above the promised fifteen cents per pound promised.

.

The latest question in the kitchen is whether the cooks shall continue to use butter for pastry purposes, at a cost from twenty-five to thirty cents per pound, or whether they shall try oleomargarine, as the artificial butter is called, and which costs only sixteen cents. Whatever may be the merits of Oleomargarine, it is certain that no domestic invention of late years has aroused so much curiosity among matrons who wish at the same time to keep a good table and economize.

.

The Cincinnati Enquirer on May 14, 1874

.

![Kristin Holt | Victorian America's Oleomargarine. The Cost of Oleo-Margarine. The Salem Monitor of Salem, Missouri on December 6, 1873. Kristin Holt | Victorian America's Oleomargarine. "The cost of butter made by this process [from beef suet] does not exceed twelve cents per pound, though it is sold in large quantities at twenty-five cents per pound." The Salem Monitor of Salem, Missouri on December 6, 1873.](https://www.kristinholt.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Cost-of-Oleo.-The-Salem-Monitor-6-Dec-1873.png)

.

If Victorian America’s Oleomargarine cost 20% less than butter, is that actually “cheaper?”

.

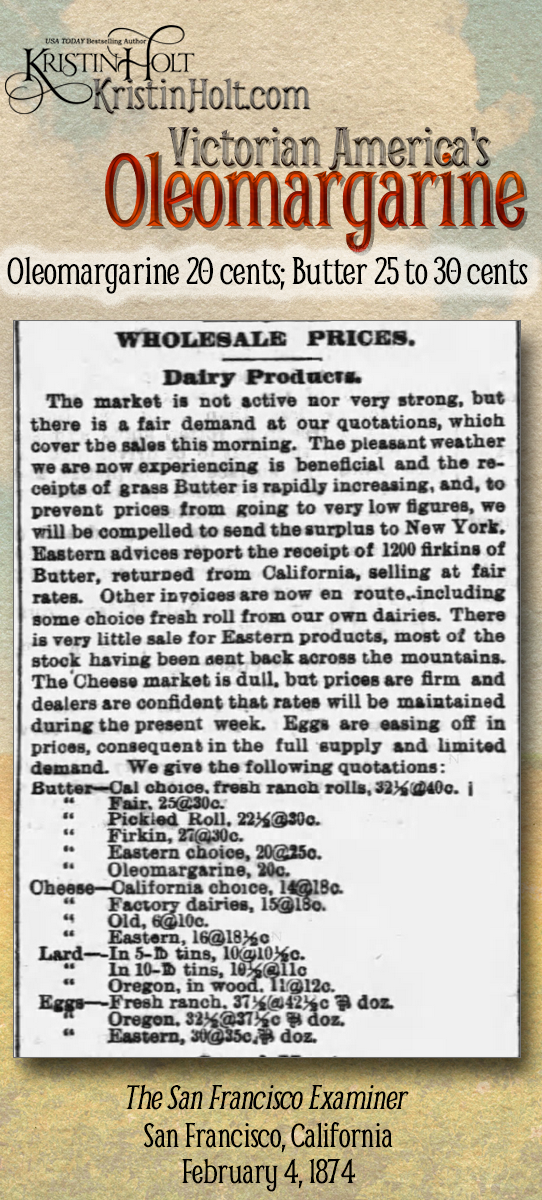

From The San Francisco Examiner of San Francisco, California (February 4, 1874): Wholesale Dairy Products Prices for butter (including Oleomargarine), cheese, lard, and eggs (by categories) with several sub-listings each. Butter prices range from 25 to 32.5 cents, while Oleomargarine is listed at 20 cents.

.

[Artificial butter] is superior, both as regards health and flavor, to a great deal of the butter used in cooking, while its cost is only one-fourth as much.

.

The Galveston Daily News on April 15, 1874

.

Galveston might have believed Oleomargarine would cost only one-fourth as much, but I’ve seen no proof.

.

PROVISIONS.

Butter (new) … 30@40c

extra, factory made…50c

Oleomargarine….30c.

Hartford Courant, of Hartford, Connecticut, October 9, 1874

.

Thirty cents a pound? Sounds terrific, right? Keep in mind that one US dollar in 1873 is more or less equivalent to twenty-two dollars in 2020. Eek. Or in reverse, today’s one dollar equals a five cents in 1873. That fake butter advertised at thirty cents a pound in 1874 Hartford? Same as a price tag of ~$7 to you and me. For bogus butter. You want the really good stuff? Try $10 per pound. No wonder homemakers wanted to at least try the new invention.

.

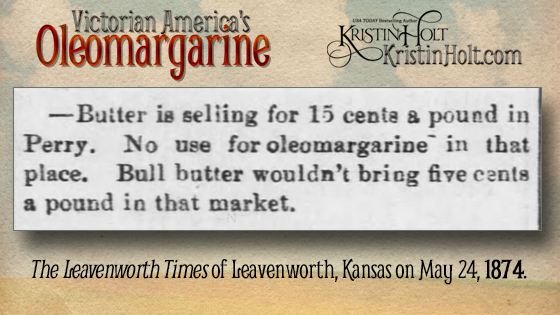

Many were absolutely not interested, no matter the price.

.

Oleomargarine: Often the Same Price as Butter

.

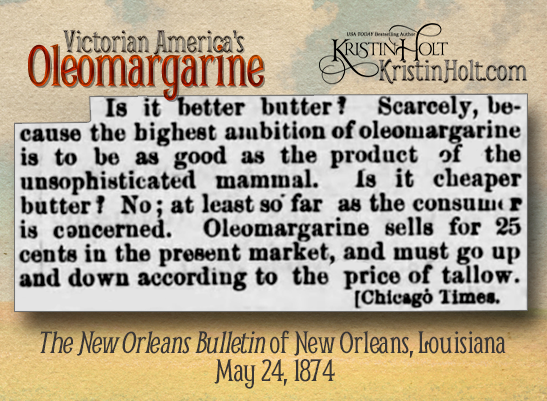

Credited to Chicago Times. From The New Orleans Bulletin of New Orleans, Louisiana. May 24, 1874.

.

Related Articles

Copyright © 2021 Kristin Holt LC

Doesn’t sound appealing, but I have heard people back in the day spread lard on their bread when the cow went dry and there was no butter. After years of eating margarine, I now stick to “the real deal” — butter. Interesting post.

Thanks for stopping by, Robyn. I’ve heard the same thing about lard as a spread on bread. I’m with you! Real butter is my personal preference.

It’s a pleasure to see you here!

Kristin