Victorian Blizzards, Nonstop in the 1880s

Victorian Blizzards, Nonstop in the 1880s

.

.

The decade of the 1880s was an uncommonly snowy, blizzard-ridden span of time in North America. Why?

.

Today is a good day to consider the famous blizzard when New York City was struck by a fierce snowstorm, as 0ne hundred twenty-nine years ago today, on March 11, 1888, the weather turned from “a brief spell of warmer weather [source]” to disastrous.

The upper Midwest (and well beyond) suffered “a string of frightfully frigid winters“ through the decade of the 1880s. The winter of 1880-81 set in early, harsh, and deep…and extended well beyond its normal boundaries.

In the three year winter period from December 1885 to March 1888, the Great Plains and Eastern United States suffered a series of the worst blizzards in this nation’s history ending with the Schoolhouse Blizzard and the Great NYC Blizzard of 1888. The massive explosion of the volcano Krakatoa in the South Pacific (in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia)) late in August 1883 is a suspected cause of these huge blizzards during these several years. The clouds of ash it emitted continued to circulate around the world for many years. Weather patterns continued to be chaotic for years, and temperatures did not return to normal until 1888. Record rainfall was experienced in Southern California during July 1883 to June 1884. The Krakatoa eruption injected an unusually large amount of sulfur dioxide (SO2) gas high into the stratosphere which reflects sunlight and helped cool the planet over the next few years until the suspended atmospheric sulfur fell to ground. (emphasis added) [source]

.

.

THE SNOW WINTER (LONG WINTER) of 1880-81

.

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s book: The Long Winter details the effects of the blizzards on the Dakota Territory of the winter of 1880-81. From various blog posts all over the internet, I read historians were so impressed by the accuracy of Laura’s remembrances–as she wrote it 60 years after it happened. The memories must’ve been extreme to remember with such vivid recall.

.

Crews clear snow along the Winona & St. Peter Railroad near Winona, Minnesota in 1881. [source]

.

The winter of 1880-1881 is widely considered the most severe winter ever known in the United States. Many children (and their parents) learned of “The Snow Winter” through the children’s book The Long Winter by Laura Ingalls Wilder, in which the author tells of her family’s efforts to survive. The snow arrived in October 1880 and blizzard followed blizzard throughout the winter and into March 1881, leaving many areas snowbound throughout the entire winter. Accurate details in Wilder’s novel include the blizzards’ frequency and the deep cold, the Chicago and North Western Railway stopping trains until the spring thaw because the snow made the tracks impassable, the near-starvation of the townspeople, and the courage of her future husband Almanzo and another man, who ventured out on the open prairie in search of a cache of wheat that no one was even sure existed.

.

Almonzo Wilder, husband of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Image: 1885, Public Domain. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

.

The October blizzard brought snowfalls so deep that two-story homes had snow up to the second floor windows. No one was prepared for the deep snow so early in the season and farmers all over the region were caught before their crops had even been harvested, their grain milled, or with their fuel supplies for the winter in place. By January the train service was almost entirely suspended from the region. Railroads hired scores of men to dig out the tracks but it was a wasted effort: As soon as they had finished shoveling a stretch of line, a new storm arrived, filling up the line and leaving their work useless.

.

There were no winter thaws and on February 2, 1881, a second massive blizzard struck that lasted for nine days. In the towns the streets were filled with solid drifts to the tops of the buildings and tunneling was needed to secure passage about town. Homes and barns were completely covered, compelling farmers to tunnel to reach and feed their stock.(emphasis added)

.

.

A snow blockade in southern Minnesota. On March 29, 1881, snowdrifts in Minnesota were higher than locomotives.

.

In September of 1881 (16th), Iowa had widespread measurable snowfall. Significant enough that the record stands as one of only two days in which snow has fallen in Iowa in the month of September. [source]

.

.

The Big Drift: 1884

.

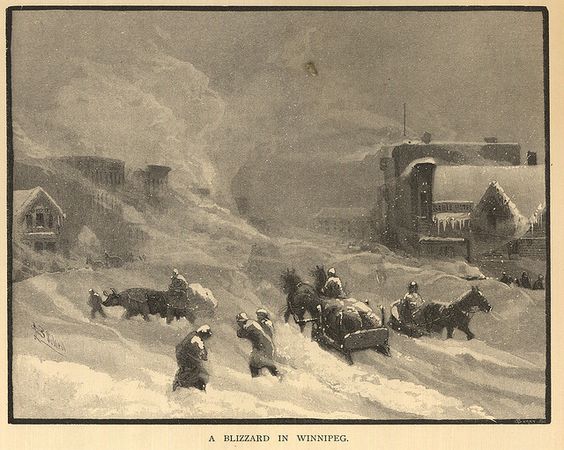

1882: A Blizzard in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Image: Pinterest.

.

.

The “Big Drift” of 1884-1885 was a cattle migration spawned by a major snowstorm on the Texas Plains that winter, pushed cattle on the open range over 600 miles, from the Arkansas River country of Colorado to the Pecos River, the Devils River and the Frio River of Texas, and resulted int he death of literally hundreds of thousands of cattle.

.

From the time that sheep and cattlemen opened the great grass lands to grazing herds, wealth of various degrees depended on the fickle elements of weather and on transportation of herds to market centers.

An entire herd of 22,000 cattle could be reduced to 80 head by a rapid drop in temperature and a high wind as happened in the blizzard of 1886.

Yet, according to Dearen, there was only one “big drift” that was greater than all the others and it is the one that occurred in the winter of 1884-1885.

“That was the big one,” said Dearen, “that eclipsed all the other cattle drifts.” [source] (emphasis added)

.

.

AN ICY MAY in Iowa (May 6, 1885)

.

1885: A late spring cold spell produced frost and flurries across Iowa from May 6-9, 1885. On the morning of the 6th it was reported that ice half an inch thick formed on standing water in Muscatine County. Flurries were reported at Sibley, St. Ansgar, and Waukon that morning and at other stations across northern Iowa on the following two days. The cold spell resulted in widespread damage to garden plants, orchards, and other vegetation across the state.[source] (emphasis added)

.

.

PLAINS BLIZZARD OF LATE 1885

.

In Kansas, heavy snows of late 1885 had piled drifts ten feet high.

.

Image of Blizzard Conditions (modern). [source]

.

.

KANSAS BLIZZARD OF 1886

.

First week of January 1886.

Reported that 80 percent of the cattle were frozen to death in that state alone from the cold and snow.

.

.

Add Tornadoes…

.

On April 14, 1886, at least 19 tornadoes touched down and ripped across Iowa. A widespread and deadly tornado outbreak ripped Minnesota, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri and Texas. Several of these tornadoes were said to produce significant damage including one that produced F4 damage, killing 3 people and injuring 18 others. This F4 tornado traveled from near Griswold, Iowa (Cass County) through Audubon and Guthrie Counties destroying most of Coon Rapids, Iowa before dissipating near Churdan, Iowa. Another tornado produced F3 damage in Taylor and Adams counties injuring at least 15 people. Further north in Minnesota, several significant tornadoes developed and probably the most notable tornado of the day was estimated to be a F4 that tore up the cities of Sauk Rapids, Saint Cloud, and Rice, Minnesota. This F4 tornado killed 72 people and injured more than 200 and caused over $400,000 in damages. In 2015 dollars, that would be roughly $10.4 million dollars. This has been Minnesota’s deadliest tornado to date. [source]

.

Sauk Rapids, MN after the devastating F4 tornado on April 14, 1886. Image courtesy Wikipedia.

Image: The Weather Whisperer, Official Blog of the NWS Des Moines Serving Central Iowa

.

GREAT PLAINS BLIZZARDS OF LATE 1886

.

On November 13, 1886 it reportedly began to began to snow and did not stop for a month in the Great Plains region.

.

The winter of 1885 and 1886 was particularly severe for Kansas settlers, says this article on Kansapedia. Image: Ice Age Now.

.

When a huge snowstorm accompanied by high winds hit the central plains in the first week of January, drifts of six feet or more were common and the temperature dropped to 30 degrees below zero in some places. The snow and wind were so fierce that people became lost a few yards from their homes. It has been estimated that nearly 100 Kansans froze to death during the storm.

.

Meanwhile, cattle turned their tails to the wind and drifted for miles across the open range until they dropped from hunger or exhaustion. Losses reached 75 percent in some areas, consequently bankrupting some large western Kansas cattle companies.

.

.

A Blizzard on the Plains, Harper’s Weekly, 1886. Image: Wyoming Tales and Trails (dot com)

.

.

GREAT PLAINS BLIZZARD OF 1887

.

January 9-11, 1887. Reported 72-hour blizzard that covered parts of the Great Plains in more than 16 inches of snow. Winds whipped and temperatures dropped to around -50F. So many cows that weren’t killed by the cold soon died from starvation. When spring arrived, millions of the animals were dead, with around 90 percent of the open range’s cattle rotting where they fell. Those present reported carcasses as far as the eye could see. Dead cattle clogged up rivers and spoiled drinking water. Many ranchers went bankrupt and others simply called it quits and moved back east. The “Great Die-Up” from the blizzard effectively concluded the romantic period of the great Plains cattle drives.

.

.

“The Longest winter: Season of 1887-88 brought deadly storms” [source]

.

.

SCHOOLHOUSE BLIZZARD

.

A.k.a. Schoolchildren’s Blizzard: hit the U.S. Plains states on January 12, 1888. The blizzard came unexpectedly on a relatively warm day, and many people were caught unaware, including children in one-room schoolhouses. [source]

.

The so-called “Schoolhouse Blizzard,” also known as “The Children’s Blizzard,” blew down from Canada and into areas that are now South Dakota, North Dakota, Nebraska, Minnesota, Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Temperatures dropped from above freezing in many areas to well below zero in a matter of a few hours. At the same time, more than six inches of powdery snow, accompanied by severe winds, blew in, creating whiteout conditions through much of the region. [source: Farmer’s Almanac]

.

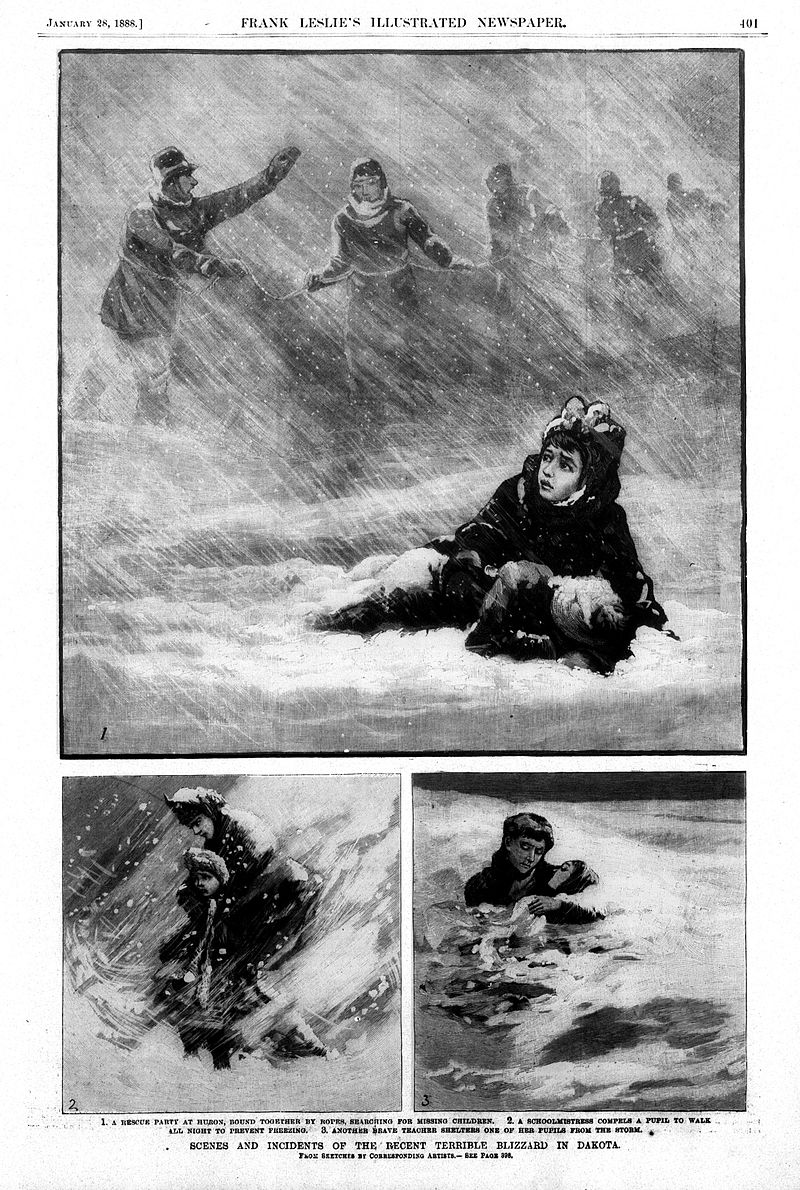

“Scenes and Incidents from the Recent Terrible Blizzard in Dakota on January 12, 1888“. – The storm came with no warning, and some accounts say that the temperature fell nearly 100 degrees in just 24 hours. The blizzard killed 235 people including many children. Frank Leslie’s Weekly, January 28, 1888. Image: Public Domain, courtesy of Wikipedia.

.

Schoolhouse Blizzard of 1888, North American Great Plains. January 12-13, 1888. What made the storm so deadly was the timing (during work and school hours), the suddenness, and the brief spell of warmer weather that preceded it. In addition, the very strong wind fields behind the cold front and the powdery nature of the snow reduced visibilities on the open plains to zero. People ventured from the safety of their homes to do chores, go to town, attend school, or simply enjoy the relative warmth of the day. As a result, thousands of people–including many schoolchildren–got caught in the blizzard. [source]

.

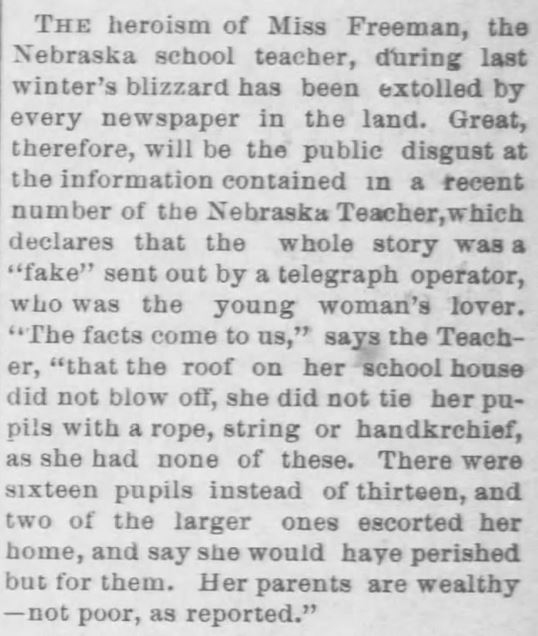

Vintage newspaper claims Miss Freeman (schoolteacher who led the children to safety during the Schoolhouse Blizzard)–was a hoax! Clark County Republican (Newspaper) of Ashland, Kansas, on May 17, 1888.

.

Seattle writer David Laskin reconstructed the storm in “The Children’s Blizzard” in 2004:

“For years afterward, at gatherings of any size in Dakota or Nebraska, there would always be people walking on wooden legs or holding fingerless hands behind their backs or hiding missing ears under hats victims of the blizzard.”

.

.

GREAT BLIZZARD OF 1888

.

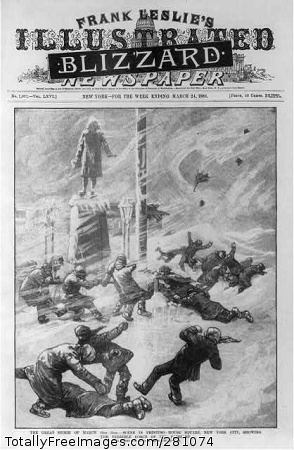

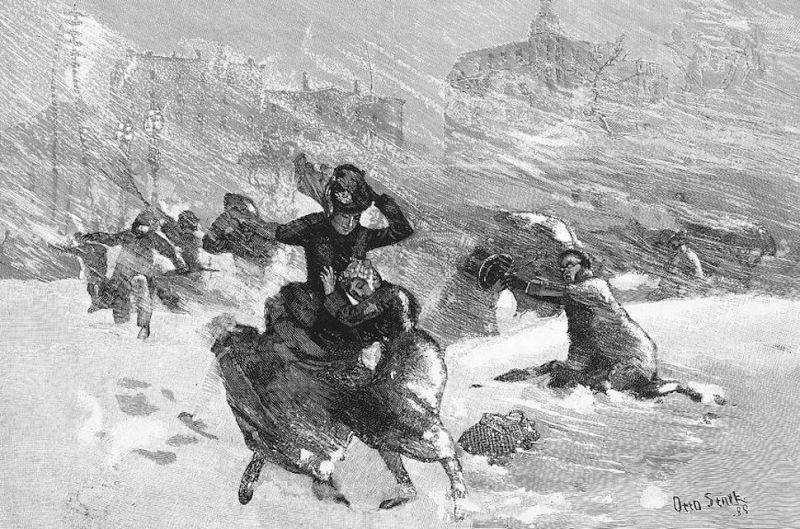

Illustration of the Great Blizzard of 1888. Original Work of the U.S. Federal Government, Library of Congress. Image: Public Domain, courtesy of Wikipedia.

.

(March 11-March 14, 1888) was one of the most severe recorded blizzards in the history of the United States of America. The storm, referred to as the Great White Hurricane, paralyzed the East Coast from the Chesapeake Bay to Maine, as well as the Atlantic provinces of Canada. [source]

.

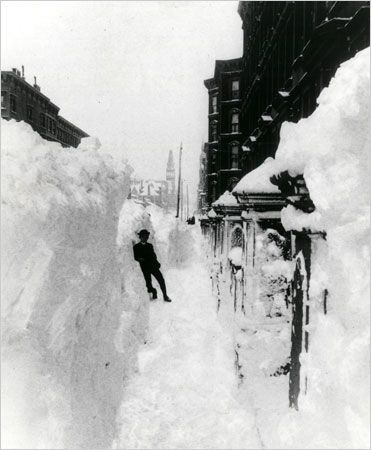

New York Blizzard, 1888. Image Source.

.

Great Blizzard of 1888 March 11-13, 1888. One of the most severe recorded blizzards in the history of the United States. On March 12, an unexpected northeaster hit New England and the mid-Atlantic, dropping up to 130 cm (50 in) of snow in the space of two days. Some 400 people died, including many sailors aboard vessels that were beset by gale-force winds and turbulent seas. In parts of New York City, snowdrifts reached up to the second story of some buildings. [source]

.

Image from New York Times. Great blizzard of 1888 in NYC. A view of Madison Avenue south from 50th Street. Image: Pinterest.

.

THE GREAT BLIZZARD OF 1888

.

The weather preceding the blizzard was unseasonably mild with heavy rains that turned to snow as temperatures dropped rapidly. The storm began in earnest shortly after midnight on March 12, and continued unabated for a full day and a half. The National Weather Service estimated this Nor’easter dumped as much as 50 inches (130 cm) of snow in parts of Connecticut and Massachusetts, while parts of New Jersey and New York had up to 40 inches (100 cm). Most of northern Vermont received from 20 inches (51 cm) to 30 inches (76 cm) in this storm.

.

Drifts were reported to average 30-40 feet (9.1-12.2 m), over the tops of houses from New York to New England, with reports of drifts covering three-story houses. The highest drift (52 feet or 16 metres) was recorded in Gravesend, New York. It was reported that 58 inches (150 cm) of snow fell in Saratoga Springs, New York; 48 inches (120 cm) in Albany, New York; 45 inches (110 cm) of snow in New Haven, Connecticut; and 22 inches (56 cm) of snow in New York City. The storm also produced severe winds; 80 miles per hour (129 km/h) wind gusts were reported, although the highest official report in New York City was 40 miles per hour (64 km/h), with a 54 miles per hour (87 km/h) gust reported at Block Island. New York’s Central Park Observatory reported a minimum temperature of 6°F (14°C), and a daytime average of 9°F (13°C) on March 13, the coldest ever for March. (emphasis added)

.

.

New York City, Blizzard of 1888. Source.

.

March 11-14, 1888

More than 120 winters have come and gone since the so-called “Great White Hurricane,” but this whopper of a storm still lives in infamy. After a stretch of rainy but unseasonably mild weather, temperatures plunged and vicious winds kicked up, blanketing the East Coast in snow and creating drifts up to 50 feet high. The storm immobilized New York, Boston and other major cities, blocking roads and wiping out telephone, telegraph and rail service for several days. When the skies finally cleared, fires and flooding inflicted millions of dollars of damage. The disaster resulted in more than 400 deaths, including 200 in New York City alone. In the decade that followed, partly in response to the 1888 storm and the massive gridlock it wrought, New York and Boston broke ground on the country’s first underground subway systems. [Source: History.com]

.

THE BURIED CITY; A NIGHT OF DEVASTATION, How The Tempest Howled and Raged Through the Dark Wilderness Streets; Perishing Men and Women.

~ The New York Herald of March 14, 1888, quoted by NBCNewYork.com

.

Newspaper from March 1888. Source.

.

… the worst storm the city has ever known. [New York was] helpless in a tornado of wind and snow which paralyzed all industry, isolated the city from the rest of the country, caused many accidents and a great discomfort and exposed it to many dangers.

~ The New York Times on March 13, 1888, quoted by NBCNewYork.com

.

Carts haul snow and ice, cleared from city streets, to the river for dumping in the East River in New York, possibly during the Blizzard of 1888. (Photo by Buyenlarge/Getty Images) Image: Pinterest.

.

The blizzard raged from March 11 to March 14. The New York Public Library archives estimated that 200 people died in New York City. The New York Times reported that 21 inches of snow fell in three days, with winds reaching 85 miles an hour.

.

The New York Herald called the storm the “Great White Hurricane.” In an accompanying article on March 13, the newspaper reported: “A great white hurricane roared all day through New York yesterday and turned the comfortable city into a wild and bewildering waste of snow and ice.”

.

.

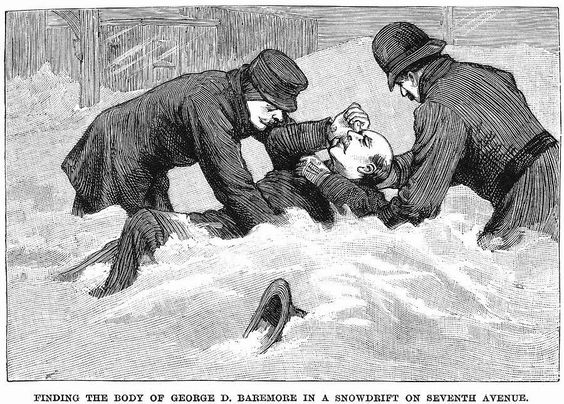

THE BLIZZARD OF 1888 changed everything in New York City. The storm was so devastating that certain streets were blocked for days. More horrifying still, due to the hurricane-force winds, many people had been knocked unconscious and were subsequently buried in the snow. Hundreds of dead animals were found underneath the massive snow drifts. Image: Pinterest.

.

.

.

Related Articles

.

Updated March 2022

Copyright © 2017 Kristin Holt LC

Victorian Blizzards, Nonstop in the 1880s Victorian Blizzards, Nonstop in the 1880s Victorian Blizzards, Nonstop in the 1880s