No Matter How You Say It…

Have you ever stumbled across a turn of phrase (hold your horses, for instance) in a western historical romance and wondered if it fit?

Had the phrase been coined?

… or did you jump the gun?

.

……………………

.

No Matter How You Say It…

.

While writing my past few western historical romances, I’ve taken the time to look up most of these phrases. I probably missed some. I want to share a handful with you here, along with the history behind that common phrase (colloquialism), when it came to be, and how we know that origin.

.

WHAT IS A COLLOQUIALISM?

.

Image: Courtesy of Google.

.

Now, off to the list used in my most recent novella, Pleasance’s First Love, in alphabetical order, rather than in order in which they appear (’cause that would be just too complicated):

.

A BIRD IN THE HAND IS WORTH TWO IN THE BUSH

.

This one feels old-fashioned. Like it’s been around a while. I almost didn’t look it up.

Meaning: It’s better to have a lesser but certain advantage than the possibility of a grater one that may come to nothing.

Origin: This proverb refers back to medieval falconry where a bird in the hand (the falcon) was a valuable asset and certainly worth m ore than two in the bush (the prey).

The first citation of the expression in print in its currently used form is found in John Ray’s A Hand-book of Proverbs, 1670, in which he lists it as: A [also ‘one’] bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

[source]

.

BY YOUR LEAVE

.

This one felt plenty old too. After all, my title was set in 1879. This sounds incredibly medieval, but it’s still used today. Haven’t you heard, “without so much as a by your leave, he walked out.”

Meaning: Choosing to not ask permission

Origin: ‘Without so much as a by your leave’ is an old phrase but is still often used when someone, who might have been expected to have asked permission first, is disapproved of for acting on their own authority. … expression began life in the early 19th century. The first mention that I can find of a version in print is from The New-England Magazine Volume 3, September 1832: The evil creature [a mosquito] … lit upon my forehead. Already he had inserted his atrocious tube, and was drawing blood, without so much as the civility of By your leave.

[source] <— Check this source out for a great deal more information–and it’s most entertaining and enlightening (this singular page)

.

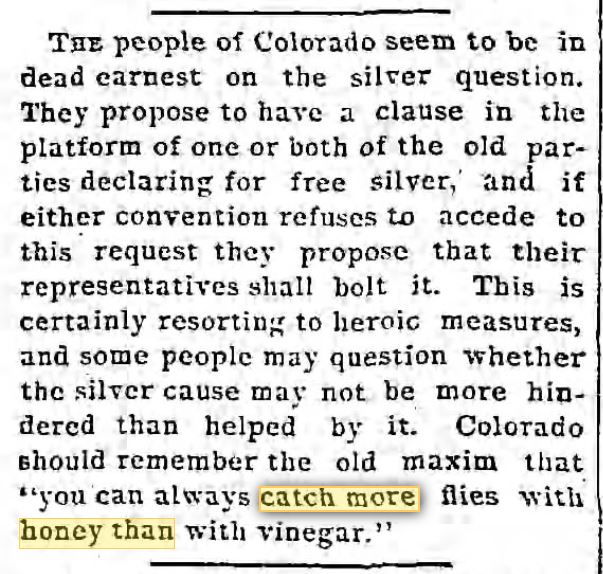

CATCH MORE FLIES WITH HONEY THAN WITH VINEGAR

.

I’ve heard my mother say it, her mother say it, and I understand her mother said it. It feels like something our great-great grandmothers would’ve used in their repertoire, warning others to be kind and gracious in asking somebody else to do something for them. You’ve heard this one, at least occasionally, haven’t you?

Interestingly enough, it’s not simple or easy to find this phrase online, with a definitive source saying “Yep, definitely used pre-1879”, so I just went with it. Dangerous, I know. { wink }

.

I found it!

…The proverb has been traced back to G. Torriano’s ‘Common Place of Italian Proverbs’ . It first appeared in the United States in Benjamin Franklin’s ‘Poor Richard’s Almanac’ in 1744, and is found in varying forms…” From “Random House Dictionary of Popular Proverbs and Sayings” by Gregory Y. Titelman (Random House, New York, 1996).

[source] Note: this book is old enough, hard covers are literally 1¢, plus shipping

.

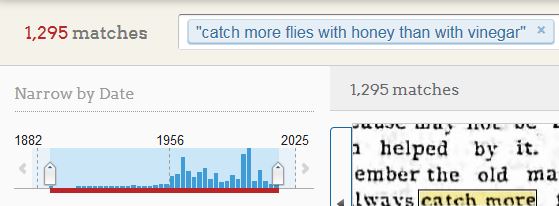

Interesting, isn’t it, that a matching reference doesn’t show up in newspaper archives until nearly turn of the century?

.

The Los Angeles Times of Los Angeles, California, on April 27, 1892. Old, but not old enough for 1879. Oops. But…unless it makes a reader stop and say hmmmm (such as “Golly Gee, Batman, ya think?”), it’s not likely to trip up any but the most astute of language historians.

.

And…just because my search today on Newspapers.com didn’t turn up anything older than this snip from The Los Angeles Times doesn’t mean there aren’t older uses. Newspapers.com is constantly adding new editions, new papers, filling in spaces that had previously been blank. When researching Belle Gunness (a fascinating serial-murderer of a woman who killed multiple mail-order husbands), I asked Newspapers.com to alert me when new references were made available. I’ve received at least two dozen emails from them reporting 2,3, 10, 12, 20 (each time) more references than once existed in their databases.

.

Newspapers.com search, showing frequency of matches for “catching more flies with honey than with vinegar“, along with a timeline (years). It’ll be interesting to see if more identifications, from earlier years, appear as Newspapers.com obtains more issues, more historic newspapers, and fills in all the gaps.

.

CUT AND RUN

.

Meaning: To “cut and run” means, of course, to make a hasty departure, usually a retreat under fire, abandoning any further effort in order to escape a difficult situation.

Origin: One might imagine a number of possible sources for the “cut” of “cut and run,” and your guess about “cut your losses” (to cease or quit a hopeless enterprise or situation before losses become greater) is a good one. But the roots of “cut and run” actually lie in the days of sailing ships. A ship at anchor coming under sudden attack by the enemy, rather than waste valuable time in the laborious task of hoisting its anchor, would sacrifice the anchor by cutting the cable, allowing the ship to get under sail and escape the attack quickly.

“To cut and run” was thus an accepted military tactic in emergencies, and the phrase itself dates to at least the early 1700s. By the mid-1800s, “cut and run” was in common use as a metaphor for abruptly giving up an endeavor in the face of difficulty, and appears in non-nautical context in Dickens’s 1861 novel Great Expectations.

[source]

.

EATING CROW

.

Meaning: Eating crow is an American colloquial idiom, meaning humiliation by admitting wrongness or having been proven wrong after taking a strong position. Crow is presumably foul-tasting in the same way that being proven wrong might be emotionally hard to swallow.

Origin: The exact origin of the idiom is unknown, but it probably began with an American story published around 1850 about a slow-witted New York farmer. Eating crow is of a family of idioms having to do with eating and being proven incorrect, such as to “eat dirt” and to “eat your hat” (or shoe), all probably originating from “to eat one’s words”, which first appears in print in 1571 in one of John Calvin’s tracts, on Psalm 62: “God eateth not his words when he hath once spoken.”

[source]

.

.

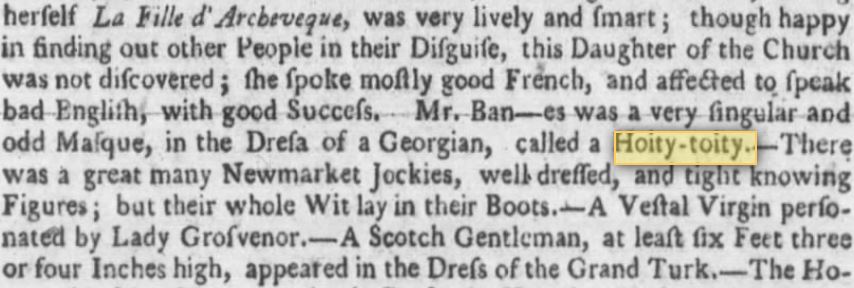

HOITY-TOITY

.

Meaning: The expression comes from our penchant for creating rhyming phrases such as “loosey-goosey” or “helter-skelter,” and in this case its base is “hoit,” an obsolete 16th century verb whose meaning is “to play the fool” or “to indulge in riotous and noisy mirth.” (“Hoity-toity” was more commonly used to describe those who engaged in thoughtlessly silly or frivolous behavior before it became more of a synonym for “pretentious.”)

[source]

.

Hoity-Toity used in The Virginia Gazette of Williamsburg, Virginia, on July 23, 1772.

.

HOLD YOUR HORSES

.

Meaning: “Hold your horses”, sometimes said as “Hold the horses”, is a common idiom to mean “hold on” or wait. The phrase is historically related to horse riding, or driving a horse-drawn vehicle.Â

Origin: There are several sources documenting the usage of “hold your horses” in–

Literal meaning:

- In Book 23 of the Iliad, Homer writes “Hold your horses!” when referring to Antilochus driving like a maniac in a chariot race that Achilles initiates in the funeral games for Patroclus

- During the noise of battle, a Roman soldier would hold his horses

- After the invention of gunpowder, the Chinese would have to hold their horses because of the noise

Idiomatic meaning:

- A 19th-century USA origin, where it was written as ‘hold your hosses’ (“hoss” being a US slang term for horse) and appears in print that way many times from 1843 onwards. It is also the first attested usage in the idiomatic meaning. Example: from Picayune (New Orleans) in September 1844, “Oh, hold your hosses, Squire. There’s no use gettin’ riled, no how.”

- In Chatelaine, 1939, the modern spelling arises: “Hold your horses, dear.”

- The term may have originated from army artillery units. Example: Hunt and Pringle’s Service Slang (1943) quotes “Hold your horses, hold the job until further orders”

[source]

.

LET SLEEPING DOGS LIE

.

Meaning: He [Sir Robert Walpole (next paragraph)] was quoted as saying this on more than one occasion regardless of whether it had to do with matters of the King’s Court, the American Revolution or any other situation where difficulties had arisen.

Origin: The saying “let sleeping dogs lie” was a favourite of Sir Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Great Britain, who exercised considerable influence over King George I as well as King George II from 1721 through to 1742.

That being said, the Book of Proverbs (26:17) says:

He that passes by, and meddles with strife belonging not to him, is like one that takes a dog by the ears.

In other words, the saying “let sleeping dogs lie” has its roots in the Bible.[source]

.

PIGHEADED

No Matter How You Say It…

Meaning: stupidly obstinate; stubborn: pigheaded resistance.

Origin: Origin of pigheaded

1610-1620 1610-20; pig1+ -headed

Related forms

pigheadedly, adverb

pigheadedness, noun[source]

.

ROSE TINTED GLASSES

.

Meaning: The meaning of “looking through rose tinted glasses” is to see only good things, only the best parts of the view, only the positive attributes etc., as supported by this www.thefreedictionary.com definition: rose-tinted glasses (British, American & Australian) also rose-tinted spectacles (British) if someone looks at something through rose-tinted glasses, they see only the pleasant parts of it She has always looked at life through rose-tinted glasses.

Origin: A Google Books search finds four instances of “rose-colored glasses” from the years before 1850.

From Mary Boddington, Slight Reminiscences of the Rhine, Switzerland, and a Corner of Italy (1834):

O the joy of blossoming life! What a delicious thing it is to be young, and to see everything through rose-coloured glasses ; but with a wish to be pleased, and a certain sunniness of mind, more in our power than we imagine, we may look through them a long time. When the sun shines, and the earth holds a bright holiday, I still feel as if life and hope were all before me, and yet the story i told out and out as far as belongs to dreams and fancies ; and yet I dream on, and love flowers, and air, and sunshine, as if I was but just beginning life. [sic].

From Mary Davenant, “The Ideal and the Real,” in Godey’s Lady’s Book (October 1843):

“A man in love is easily deceived. I have seen more of life than you have, my dear, simply because I look at people with my own eyes, instead of through rose-coloured glasses as you do, and I never see a woman who appears so very soft and gentle that she cannot raise her voice much above a whisper, and whose every word and look betrays a studied forethought of the effect they are to produce, that I do not mistrust her sadly. Half of them re shrews, and the other half obstinate intriguers–I am much mistaken if Mrs. St. Clair is not a little of both.” [sic]

.

From “Elliotson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine,” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (December 13, 1843):

The gentleman last named in the above somewhat extended overture to the work before us, is an old and valued personal friend of the writer of this brief notice. We have studied with him, ausculted with him, travelled with him, and in all these relations he has been among our most esteemed associates. If there were some good reason for valuing his talents and acquirements in the days of our personal intercourse, there is the same reason for hoping that he would not have published a book without merit, and that his friend need not be obliged to look at his labors through the rose-colored glasses of personal kindness to see them under a favorable aspect. [sic]

.

From W.A., Fewell: A Series of Essays of Opinion for Churchmen (1846):

But, however, looking at the position of the clergyman under this system, it is manifestly a temptation of that position to strive after popularity ; to be easy and compliant ; to inquire but little; and to permit the decencies, and suitabilities, and respectabilities of society to take the place of discipline–in short to see every thing rose-color; and if rose-color be not there, to put upon his nose rose-colored glasses..

These four instances show the range of attitudes that can be encompassed by the phrase. In Boddington’s travel memoir, rose-coloured glasses are a kind of natural sunniness of outlook that goes some way toward transforming the world into the optimistic image of it that the young person has. In Davenant’s story, the glasses are a source of deception for the wearer, who leaves common sense behind when he puts them on. In the review of “Elliotson’s Principles,” the glasses are a form of intentional self-delusion, committed out of sentiment or personal friendship, that prevents an honest critical appraisal. And in W.A.’s essay for churchmen, wearing rose-colored glasses entails denying or ignoring unpleasant truths in order to be liked. [sic]

.

Yet another attitude appears in “Quackery,” in The St. James’s Medley (May 1865):

A lover of fiction, and of vivid fancy, he [the auctioneer] flourishes his hammer, and by its transmuting touch converts a tumble-down cottage in a swamp into an elegant and commodious villa on the bank of a beautiful river. He considers it his duty to make the best of everything, viewing it through rose-coloured glasses; and if he does represent this or that article to be in better condition, or more valuable than it is, he does but exercise a legitimate trickery, which he considers to be the high art of his profession..

Here the rose-coloured glasses are, in effect, shared by the huckster with his audience of potential rubes: He wears them to describe the imaginary beauties of the things he is trying to sell, and the audience wears them to imagine that what he says is true. [sic]

[source]

.

RUN FOR ONE’S (YOUR) MONEY

.

Meaning: The Oxford English Dictionary suggests that the origin was in horse racing, which, like English hunting, can be a costly sport. But almost from the start the phrase could be used in a figurative or extended sense, to mean any sort of challenge, with or without any money being spent. Indeed, the first use cited by the OED gives the phrase in its figurative use.

Origin: “1874 Slang Dict. 274 To have a run for one’s money is also to have a good determined struggle for anything.”

[source]

.

SAM HILL

.

Meaning: used in exclamations as a euphemism for “hell”; “what in Sam Hill is that smell?”

Origin: mid 19th century: of unknown origin

[source]

.

In Closing

.

And there you have it. A list of various colloquial idioms that made an appearance in Pleasance’s First Love, set in 1879, Colorado Rocky Mountains (in and near Leadville). This title is part of the highly rated 12-book series, Grandma’s Wedding Quilts.

.

Invitation

.

What do you think? Do colloquial phrases such as these, in western historical romance (or other historical fiction) bug you when they “feel” or “seem” too new?

Have you ever paused to look them up?

Do any of these surprise you?

Please scroll down and respond. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

.

………………………………………………….

.

Related Articles

No Matter How You Say It…

No Matter How You Say It…

Updated August 2022

Copyright © 2017 Kristin Holt LC